Although I have been studying, teaching and writing about collective trauma for many years, I had a breakthrough of understanding recently. In June, I joined a group of 150 people from 39 countries who traveled all the way to Israel to begin a deep and rich training about Collective Trauma (CT) and its impact on our social psychology.

And I learned some things I think I had to leave the country to see more clearly. Namely, the extent of the Collective Trauma of war in the US and its impact on our veterans, me being one of them. I also learned how therapists (including me) often unwittingly perpetuate the CT by leaving their veteran clients continuing to carry the burden of our country’s CT alone since few of us are willing to carry our responsibility.

If we let ourselves see and understand the full CT of war, we will understand that we cannot simply stay in our professional role as a therapist. Collective Trauma carries forward in part by our talking about it once-removed as a concept, and by using sentences that separate us from being fully part of it. This is an attempt to take us off the hook, to look like we are engaging it when we really aren’t.

To be a healing force in the life of a veteran, we therapists must face the CT of war in ourselves. As therapists we know that you can never heal trauma at a distance, even with great understanding and insight. So we need to find places to talk about it in the first person, on a very personal level, in order to help our veteran clients face it in their lives and not leave them having to try and process the country’s CT solely through their individual, personal trauma.

The following is my personal story as I am both a veteran and a therapist…

During the conference in Israel, many participants from around the world spoke painfully about how current or past wars were impacting their country. These people knew, so much better then most Americans, that the trauma of war reaches far beyond soldiers of one group killing the soldiers of another group. It greatly affects the civilian population, the villages, towns and cities where they live, and the environment where they farm and interact with the natural world. This destruction is commonly referred to, and often dismissed, as “collateral damage”.

As the days wore on, I began to notice the language being used: people often spoke of war but rarely used the word “soldiers” or “men.” They would talk about how “In the war women were used as tools.” or “The war left our country with very few young people.” Note the absence of the words “soldiers” or “men” who, of course, were the ones that used the women as tools and who killed the young people.

Several times a day we would break into triads to process any emotional material that was personally arising in us. I frequently talked about my experiences as a Marine in Vietnam and the myriad feelings that were coming up for me. But no matter how much any person knew about me being a former soldier who had fought in Vietnam (a war most people around the world consider an atrocity), when they talked about war and its CT, it was always in the abstract. The part of me that had been in war as a soldier never seemed present, let alone welcomed, into the conversation.

I slowly realized that my being a soldier who had taken part in something as horrible as Vietnam would have brought a tension into conversations that were being avoided by everyone. I could be an individual who had suffered from the realities of war, with everyone focusing on the pain I carried, but never on the pain that I had caused. They wouldn’t, or couldn’t, acknowledge me as a soldier that caused suffering to others. So language was used that kept all of us once-removed from the tension and trauma in our midst.

Upon reflection I could see that the same thing has happened with every therapist I have worked with around my trauma in war. They would frame the issue as an individual one for me, highlighting how horrible it was for me to have taken part in war. They would focus on my personal trauma, before and during the war, and my PTSD after the war.

Not one of them helped me face my responsibility for having taken part in the atrocity of Vietnam or for the specific harm I did to the Vietnamese, at least in any way that focused on the civilian victims of our military violence or what we did as a country in the totality of that war. Partial excuses were made: I was a teenager at the time; the war machine left soldiers no choice but to follow orders, I acted as humanely as possible, etc.

Whenever I left therapy I always felt good about how I had dealt with my PTSD around war, and felt glad for “having done my work.” However, I left dissociated from my place in the traumatizing of the Vietnamese people by being part of the immensity of the collateral damage. Therapy had helped me feel better about myself, but also helped me dissociate from my (and this country’s) responsibility for doing so much harm.

It might have happened again in this conference, this false removal of me as a soldier who took part in causing such significant CT, since the conversations continued using abstractions about the impact of war and avoided speaking of soldiers and men. However, it continued long enough and wore me down so much that I couldn’t escape the truth. No matter how much they or I tried to separate myself from those groups of soldiers that had done harm, no matter how much they or I tried to erase that part of myself, I could feel it was always a lie.

It became clear that everyone wanted to avoid seeing me as a man that had been a soldier so they could avoid the emotional turmoil it would bring up in them if there was an undeniable former soldier in their midst. It was confusing. And it left me feeling more and more ashamed and alone.

I could understand why people from countries where war was a current or recent issue would not want to feel the trauma of what soldiers had recently done in their country, but I couldn’t understand why all the Americans were refusing to use a language that held the reality that I was a soldier in our military that had done harm.

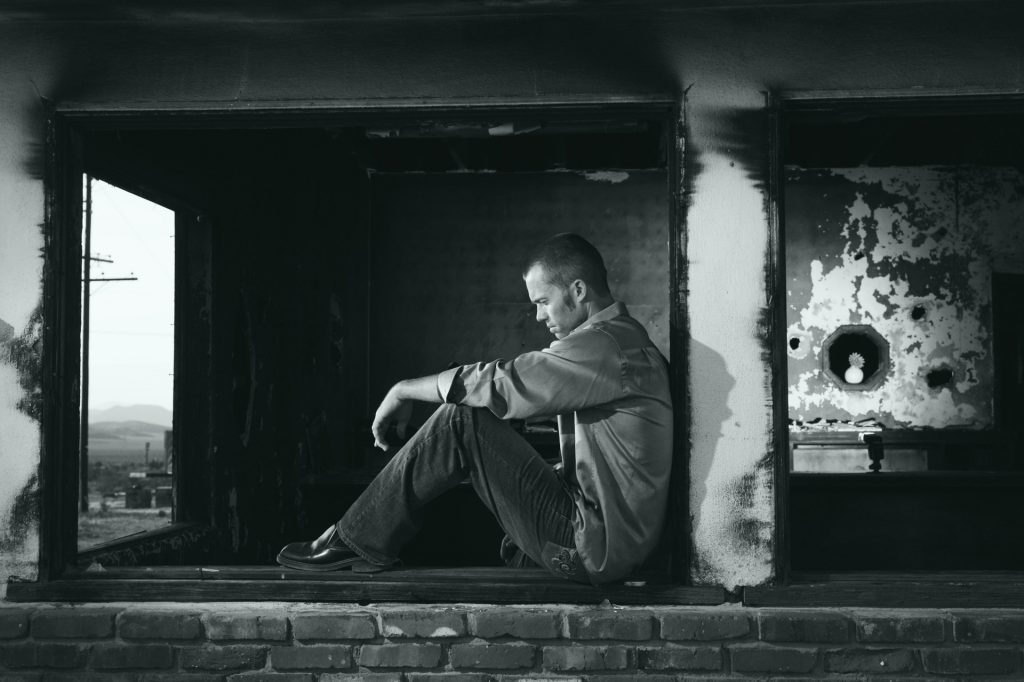

To feel like this part of me was invisible was incredibly disturbing for me. I was left feeling emotionally collapsed inside and filled with deep shame and wishing I could hide (which is not uncommon for many vets). But thankfully, out of desperation, I spoke about this with a Palestinian psychiatrist participant who said to me, “Everyone is always drawn to the victim inside or outside of himself or herself, but no one really wants to take responsibility for their part in Collective Trauma.”

I then got a lightening bolt of clarity and a feeling of outrage! What the Americans at the conference, and everyone back home, had been turning away from wasn’t just me as a soldier who had fought in Vietnam, but their own responsibility in that unjust and horrible war. Not one of them would stay present with me and hold the responsibility that they carried for that war or any of our wars, regardless of their own personal feelings about war.

They wouldn’t face that they, as American citizens, had essentially asked me to go fight for our country. That they had bought my uniform, put a gun in my hands, given me the bullets to put in the chamber, and sent me off to war. And then they turned their back on me when I came home and hoped I would never tell them what WE did there. The blind comfort they felt without understanding the collateral damage that their taxes made possible essentially left the burden of responsibility on all veterans and me.

And this is where, as a therapist, I have a new understanding about how we can cause harm to our veteran clients, however unwittingly. I now see that my therapists couldn’t sit with that part of me, the soldier that did harm, because they couldn’t sit with that part of themselves that held some responsibility for that harm. So I was never able to fully heal.

I was left vulnerable to getting my trauma triggered by other people’s response to Collective Trauma. Their refusal to take responsibility for the harm caused during our wars left them with guilt, shame, anger, sorrow, whatever, which got triggered upon learning that I was a veteran. And this took them away from not just me but themselves. But it left me confused and feeling it was me they were turning away from.

And I can see how my suffering as a veteran, and that of all veterans, becomes exacerbated when we feel this turning away, since this leaves us isolated and left to carry the entire weight of our shared responsibility for the Collective Trauma of the war we fought in.

It would have been so powerful, helpful and healing had any one of my therapists been able to say, “Patrick, I am having such a hard time sitting with you right now as you talk about the harm you did in Vietnam. What is hard is that I can see that to help you heal I cannot stay in my safe role as a therapist. I have to show up also as a citizen of this country that sent you to war and then turned my back on you and my responsibility in that war so I could stay comfortable. Because to stay in my role as a therapist will leave you trying to heal from something we are both responsible for.”

Hearing words like these could have helped me shatter the aloneness and shame I have carried since 1971. Thankfully, three American women said just that to me before I left Israel and it changed my life and how I walk with war. Maybe now that I know how the Collective Trauma of war hides in all of us, I will be able to be of greater service to my veteran clients. Because I now see how I, like most therapists, have also avoided taking responsibility as a citizen for the wars since Vietnam.

It is my hope that if we all take on our share of responsibility, we will no longer force veterans to carry the full weight of our collective trauma alone. And also that if more of us become fully responsible citizens we will have fewer wars that create veterans, launch fewer drones and airstrikes, and cause less collateral damage.

Originally published at https://www.mntraumaproject.